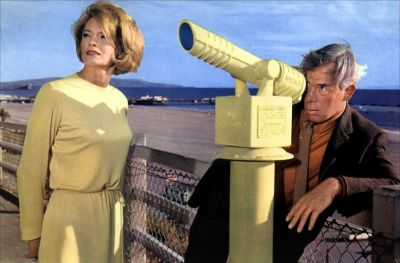

POINT BLANK

(Senza un attimo di tregua, USA/1967) R.: John Boorman. D.: 92'. V. inglese

Alla presenza di John Boorman

Precede

HOW A MOSQUITO OPERATES (USA/1912) R.: Winsor McCay. D.: 6'

Accompagnamento al piano di Donald Sosin

Nell'improvvisa rinascita del cinema noir statunitense, a metà degli anni Sessanta, Point Blank, film di gangster, si distingue facilmente dalla saga dei detective privati, come P.J. Harper, Tony Rome e Peter Gunn. È, se si vuole, l'esito estremo, e a tutt'oggi insuperato, di una tendenza avviata da Contratto per uccidere di Don Siegel, dove trovavamo già riuniti Lee Marvin e Angie Dickinson [...]. Era l'apparizione dell'assassino glaciale, una vera macchina di morte, di cui Johnny Cool era un'altra incarnazione. Con il mondo del detective privato mostrato in quello stesso periodo da Jack Smight o Gordon Douglas, Blake Edwards o John Guillermin, si ritornava alla psicologia, alla satira di costume, al quadretto pittoresco, un registro romanzesco dove il groviglio dei rapporti umani si rifletteva nella complessità dell'intrigo. Point Blank, al contrario, si sottrae alla caratterizzazione e alla psicologia, riduce le motivazioni all'essenziale, ignora le storie tortuose e sfocia con naturalezza nella fiaba. L'adozione del flashback da parte di Boorman, lungi dall'essere gratuita a causa dell'influenza europea, come gli hanno rimproverato alcuni, non fa che riallacciarsi alle tendenze generali del racconto. I ritorni al passato sono molto diversi da quelli che si incontrano nei polizieschi classici. Il loro valore esplicativo è sottile: le informazioni che ci svelano avrebbero potuto essere fornite con due o tre frasi di dialogo. Nessuna psicologia ma una forza poetica e fisica. Point Blank all'apparenza sembra una storia di vendetta. E lo è fino in fondo. Ma non è sbagliato vedervi anche un apologo più complesso, un quadro simbolico dell'America. [...] La struttura circolare del racconto riesce a conferire all'insieme un'impressione d'irrealtà, o di una realtà filtrata dal sogno, di una luce attenuata dal ricordo, come suggeriscono alcune inquadrature velate di Lee Marvin. Il film si conclude sulle mura in pietra della prigione abbandonata e sull'acqua del fiume, sulle luci lampeggianti nella notte, come se si concretizzassero le parole della guida sul battello quando dichiarava ai turisti che le perfide correnti intorno all'isola rendono impossibile l'evasione. Catturato nel gorgo di una tempesta che egli stesso ha provocato, Walker non sfugge al proprio incubo. L'impressione onirica è accentuata dallo sdoppiamento della moglie di Walker che, morta, sembra reincarnarsi nella sorella (e la scelta di Sharon Acker e Angie Dickinson, fisicamente somiglianti, fu deliberatamente voluta da Boorman).

(Michel Ciment, John Boorman, un visionnaire en son temps, Calmann-Lévy, Paris 1985)

Though belonging to the unexpected revival of the Hollywood thriller in the mid-Sixties, a gangster film like Point Blank is easily distinguishable from the concurrent 'private eye' cycle, represented by such titles as P.J. Harper, Tony Rome and Peter Gunn. It is, in a sense, the extreme - and, to this day, unsurpassed - culmination of a phenomenon first seen in Don Siegel's The Killers which also co-starred Lee Marvin and Angie Dickinson [...]. The apparition of the ice-cold, robotic killer, of whom Johnny Cool was yet another incarnation. The world of the private eye, latterly illustrated by Jack Smight and Gordon Douglas, Blake Edwards and John Guillermin, engendered a return to 'psychology', to social satire and the picturesque, to a brand of story-telling in which the intricacy of human relationships was rivalled only by the complication of the plot. Point Blank, by contrast, plays down both characterization and psychology, reduces motivation to the absolute essential and dispenses with labyrinthine subplots, thereby, quite naturally, acquiring the stark linearity of a fable. And if Boorman's use of flashbacks was criticized in certain quarters as gratuitous and too patently 'European' in influence, we can now see how integral they are to the overall narrative thrust. In fact, they serve a wholly different function from those found in traditional thrillers. Their expository value is virtually nil: the information which they contain might just as well have been conveyed in two or three lines of dialogue. What they do possess, however, is a visual immediacy that is as poetic as it is sheerly physical. Superficially, Point Blank would appear to be just a story of vengeance. And it is that, certainly, from beginning to end. But it's also possible to interpret it as a more complex allegory, as a symbolic portrait of the United States [...]. The circular construction of the narrative, moreover, eventually lends the whole film an aura of unreality, or of reality filtered through dreams, of lighting suffused by memories - as is suggested by certain gauzy images of Lee Marvin. Its closing shots - of the abandoned prison and its stone walls, the water of the river and the lights twinkling in the night sky - would 262 appear to confirm the words spoken by the guide on a sightseeing steamer: that the treacherous currents encircling the island preclude all possibility of escape. Caught in the whirlwind of a storm which he himself has raised, Walker can no more easily escape from his nightmare. This dreamlike atmosphere is reinforced by the doubling of Walker's wife Lynne, who appears to have been reincarnated in her sister Chris (and the casting of Sharon Acker and Angie Dickinson, who physically resemble each other, was a deliberate ploy on Boorman's part).

(Michel Ciment, John Boorman, Faber and Faber, London-Boston 1986)

Tariffe:

Ingresso libero