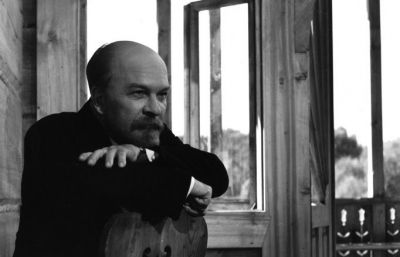

LENIN W POLSCE

(Lenin in Polonia/Lenin in Poland, Polonia/1965) R.: Sergej Jutkevicˇ. D.: 96'. V. polacca

T. it.: Lenin in Polonia T. int.: Lenin in Poland. Scen: Yevgeni Gabrilovich, Sergej Jutkevič. F.: Jan Laskowski. M.: Janina Kondzioła, Klaudia Alejewa. Scgf.: Jan Grandys. Mus.: Adam Walaciński. Int.: Maksim Strauch (Vladimir Ilich Lenin), Anna Lisyanskaya (Krupskaya), Antonina Pavlycheva (la madre di Krupskaya), Ilona Kuśmierska (Ulka), Edmund Fetting (Honecki), Krzysztof Kalczynski (Andrzej), Tadeusz Fijewski (segretario della prigione), Gustaw Lutkiewicz (investigatore), Kazimierz Rudzki (prete). Prod.: Zespół Filmowy Kadr 35mm. D.: 96'. Bn. Versione polacca / Polish version. Da: Filmoteka Narodowa per concessione di Studio Filmowe Kadr

Sergej Jutkevič, uno dei 'tre moschettieri' del FEKS (Fabbrica dell'attore eccentrico) insieme a Grigorij Kozincev e Leonid Trauberg, a partire dalla fine degli anni Trenta si dedicò alla celebrazione di Lenin realizzando tre magnifici film: L'uomo con il fucile (primo film di finzione dedicato a Lenin insieme a due opere di Michail Romm), Rasskazy o Lenine e Lenin in Polonia, che dei tre è il migliore perché ci presenta finalmente un Lenin intimo, con qualche tocco umoristico. Il regista condivideva con il grande attore Maksim Strauch la convinzione che sarebbe stato stupido fare un film su un grande innovatore senza impiegare una forma innovativa: i due volevano creare una sintesi attraverso le emozioni e le impressioni poetiche. Lenin in Polonia offre la visione intima e privata di un uomo leggendario, incentrandosi non sugli eventi puramente politici ma sui pensieri e le emozioni e facendo sapientemente ricorso al monologo interiore: tutto viene visto attraverso gli occhi di Lenin, e le sue dinamiche mentali e i suoi ricordi svolgono un ruolo primario. Lenin ci viene presentato in un momento della sua vita privo di grandi eventi ma storicamente fondamentale: sono i mesi che precedono e seguono lo scoppio della Prima guerra mondiale. (Questo dettaglio offre un ulteriore punto di vista alla nostra rassegna sul 1914). Il film è simile a un muto, con la sola voce di Strauch a descrivere ciò che accade e a riflettere sul significato delle varie notizie che si susseguono. Henri Langlois doveva pensare a questo grande film quando scrisse: "Tutta l'evoluzione, tutto il profilo dell'opera di Sergej Jutkevič sta in questo rifiuto, in questo attaccamento all'idea originaria che è fondamentale per il concetto di avanguardia. La sua è l'opera di un uomo che non smise mai di cambiare pur restando assolutamente fedele al punto di partenza: sono questo perpetuo rifiuto e questa fedeltà a uniformare la sua produzione, in una molteplicità che appare ancor più complessa se si pensa che egli non tradì né rinnegò mai le idee della sua giovinezza, lasciando che maturassero con lui".

Peter von Bagh

Sergej Jutkevič, one of the 'three Musketeers' of FEKS (along with Grigorij Kozincev and Leonid Trauberg) from the late 1930s onward made the portrayal of Lenin one of his specialties, in three exquisite films: The Man with the Gun (which along with two Mikhail Romm films was the first full-scale depiction of a fictional Lenin), Tales of Lenin, and Lenin in Poland, the finest of the three. Here at last was an intimate Lenin, with humorous touches. The director shared with the great actor Maxim Strauch the conviction that it would be dull to make a film about an innovator without thinking about avant-garde form: they wanted to create a synthesis through emotion and poetic impression. Lenin in Poland presents a man behind the legend, an inner view. Purely political events are not central, but thoughts and emotions are, with a clever use of inner monologue, meaning that everything is reflected through Lenin's eyes, with his thought process and the structure of his memories playing a more important role than the events, or in this case an eventless period of his life, although it was heavy with historical meaning given that these are the months leading to WWI and immediately following the war's outbreak. (This detail thus contributes one more facet to our 1914 theme.) It is like a silent movie, with only Strauch's voice describing what happens and pondering the meaning of disparate news. Henri Langlois must have been inspired by this remarkable film when he wrote the following lines: "The entire evolution, the entire outline of Sergej Jutkevič's work lies in this refusal, in this attachment to the real spirit, that is fundamental to the idea of the avant-garde. His work is that of a man who never stopped changing, while remaining entirely faithful to his point of departure, and it is this perpetual refusal, combined with this fidelity, that gives his work unity, in a multiplicity that is all the more subtle because he never betrayed nor renounced any of the ideas of his youth, allowing them to mature".

Peter von Bagh

Precede

DODATKOWE WOLE TRAWIENNE MAGISTRA KIZIOŁŁA

(Magister Kiziołł's Additional Digestive Goitre, Polonia/1983) R.: Julian Józef Antonisz. D.: 6'. V. polacca

T. int.: Magister Kiziołł's Additional Digestive Goitre Scen.: Julian Józef Antonisz. F.: Andrzej Trojnarski. Prod.: Animated Film Studio (Cracovia).. 35mm. D.: 6'. Col. Versione polacca / Polish version. Da: Filmoteka Narodowa

Antonisz lavorò a questo film nei primi anni Ottanta, quando in Polonia vigeva la legge marziale e il paese era in piena crisi economica. A quei tempi le ideologie del progresso e dell'ottimismo erano già state respinte, e le parodie del realismo socialista e la paranoia della vita quotidiana erano tematiche ricorrenti ormai fin dagli anni Sessanta. La singolarità di questo film sta nel suo trattare il tema della divulgazione scientifica, vista all'epoca come un settore privilegiato della cultura che permetteva di accedere alla 'realtà oggettiva'. I film di allora si ingegnavano per aggirare la censura, e questo spesso incideva sugli aspetti formali. Il film, che impiega la tecnica non-camera, fu realizzato con una delle macchine progettate e costruite sul principio del pantografo dallo stesso Antonisz e colorato a mano da sua moglie Danuta Antoniszczak. Narra la storia del bio-inventore Magister Kiziołł (una sorta di alter ego dell'artista), che con autodisciplina e dedizione alla scienza sviluppa un organo supplementare che gli permette di "masticare paglia, fieno, erba, segatura, ferraglie, cartacce e perfino le notizie del telegiornale".

Antonisz worked on this film during the time of martial law in Poland in the early 1980s when the country was deep in the midst of economical crisis. It was a time when the ideologies of progress and optimism had already been rejected, and since the 1960's, parodies of socialist realism and the paranoia of everyday life had become common themes. What is unique about this film is that it addressed scientific narratives which were seen as a privileged field of culture, granting access to an 'objective reality'. It is interesting that films of this period struggled to evade censorship and it was this battle that inspired the art form. This non-camera film was made with one of the devices designed and constructed by Antonisz, based on the pantograph and hand painted by his wife Danuta Antoniszczak. It tells the story of bio-inventor Magister Kiziołł (possibly taken to be the artist's alter ego), who through self discipline and intense professional effort, develops an extra organ which "allowed him to chew on straw, hay, grass, sawdust, scrap metal, waste paper and even the daily news on television".

Tariffe:

Aria condizionata

Accesso disabili

Tel. 051 522285