MADHUMATI

(India/1958) R.: Bimal Roy. D.: 149'. V. hindi

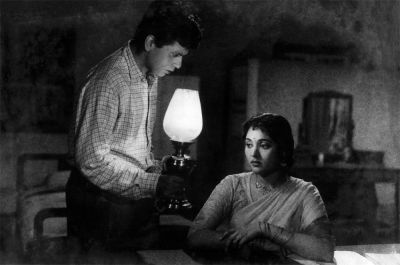

Sog.: Ritwik Ghatak. F.: Dilip Gupta. Scgf.: Sudhendu Roy. M.: Hrishikesh Mukherjee. Mus.: Salil Choudhury. Canzoni: Shailendra. Int.: Dilip Kumar (Anand/ Deven), Vyjantimala (Madhumati/Madhavi/ Radha), Johnny Walker (Charandas), Pran (Raja Ugra Narayan), Jayant (padre di Madhumati), Tiwari (Bir Singh), Mishra, Baij Sharma, Bhudo Advani. Prod.: Bimal Roy per Bimal Roy Productions

35mm. D.: 149'. Bn. Versione hindi / Hindi version

Da: National Archive of India

Madhumati, il più grande successo commerciale di Bimal Roy, è un film atipico per un regista fedele al realismo e fautore di un approccio socialista al cinema: romantica storia di reincarnazione arricchita da canzoni struggenti e da immagini suggestive, influenzò la nascita di un sottogenere del cinema hindi. Il film narra di un ingegnere che una notte trova riparo in un antico palazzo e si rende conto di esserci già stato in una vita precedente. In quella vita lavorava per il signore del palazzo e si era innamorato della splendida fanciulla tribale Madhumati.

Una creatura di nebbia

Lo straordinario risultato di Madhumati sta nel superamento delle convenzioni del film di suspense e horror gotico a favore di una fede tutta indiana nella reincarnazione e nella rinascita, con l'aggiunta di elementi derivanti dal patrimonio popolare e tribale. Il primo film significativo a esplorare questo territorio era stato Mahal (1948) di Kamal Amrohi, ma Madhumati si spinge oltre collocando il genere - che possiamo definire 'gotico indiano' - all'interno della tradizione ibrida del cinema indiano fatta di melodramma, lasciva furfanteria, umorismo popolare e sequenze di canti e danze. L'intreccio offre avvincenti colpi di scena e corre qualche rischio stimolante: il film è infestato da doppelgänger, dalla vergine tribale Madhumati alla sua apparizione spettrale, la sua sosia Madhavi, e la sua reincarnazione, Radha.

Il talento di Bimal Roy riesce a tenere in equilibrio tutti questi elementi. Maestro acclamato del realismo sociale, il regista sa delineare con estrema precisione le gerarchie del mondo di Madhumati. Osserviamo i rappresentanti di un sistema feudale avido e oppressivo, la popolazione tribale da esso sfruttata e la colta classe media urbana rappresentata da Anand, che simpatizza con i poveri ma è costretto a servire i potenti. Il tragico destino dell'eroina è in realtà "un'allegoria della misera popolazione tribale indiana" (come scrive Jyotika Virdi). La sua vendetta - la vendetta della terra contro i suoi sfruttatori - deve per forza avvenire al di fuori del regno del reale.

La sceneggiatura di Madhumati era stata scritta dal regista bengalese Ritwik Ghatak, che nei suoi film di quel periodo rivelava un interesse quasi etnografico per il mondo tribale indiano: viene da chiedersi come avrebbe scelto di presentare l'eroina se avesse diretto il film. La Madhumati di Bimal Roy è una sorta di archetipo familiare: un'innocente che personifica la natura stessa, come la Shakuntala di Kalidasa e come molte altre ninfe che popolano la letteratura e il cinema indiani. Questa astrazione ormai trita acquista una sorprendente immediatezza tra le mani di Roy. In tutto il film si percepisce la ricerca della vera natu- ra dell'elusiva e mutevole Madhumati, evocata dalla sublime sequenza in cui Anand rincorre la fanciulla in fuga nella nebbia seguendo il suono delle sue cavigliere. A questo livello il film suggerisce che stiamo assistendo all'eterno gioco del desiderio che si snoda attraverso le vite e i secoli. Come sempre nel cinema hindi, l'essenza mistica del film è affidata ai versi di una canzone: "Sono un fiume, eppure ho sete / Parole semplici, ma un profondo mistero".

Rajesh Devraj

Madhumati was Bimal Roy's biggest commercial success, a rare genre film from a director known for his realism and his socialist approach to cinema. Its romantic tale of reincarnation, ornamented with haunting songs and atmospheric visuals, was influential in establishing a sub-genre of Hindi cinema. The film tells the story of an engineer who takes shelter in an ancient mansion one night, only to realize he has been there in a previous life. He recalls that life when he worked for the lord of the mansion, and fell in love with the beautiful tribal maiden Madhumati.

A Creature of the Mist

Madhumati's striking achievement lies in transcending the conventions of the Gothic horror/suspense film to bring in a wholly Indian belief in reincarnation and rebirth, as well as elements drawn from folk and tribal lore. Kamal Amrohi's Mahal (1948) was perhaps the first significant film to explore this territory, but Madhumati goes further in placing the genre - call it Indian Gothic - within the hybrid tradition of Hindi cinema, complete with melodrama, leering villainy, folksy humour and intermittent song-and-dance sequences. The film's narrative provides several satisfying twists and turns, besides taking some intriguing risks - there is a positive infestation of doppelgangers, for instance, from Madhumati the tribal maiden to her ghostly apparition, her look-alike Madhavi, and her reincarnation, Radha.

It is Bimal Roy's skill as a filmmaker that keeps all these juggling balls in the air. An acclaimed master of social realism, he also succeeds in delineating the hierarchies of Madhumati's world quite precisely. We observe the representatives of an oppressive feudal system, the hill people it has dispossessed in its greed, and the urban educated class, represented by Anand, which sympathizes with one side, but must serve the other. The tragic fate of the film's heroine is indeed 'an allegory for India's indigent tribal population' (as Jyotika Virdi describes it). Her revenge - the revenge of the land against its exploiters - is necessarily outside the realm of the real.

Madhumati's story was written by the Bengali director Ritwik Ghatak, whose own contemporaneous work reveals an almost ethnographic fascination for the world of the Indian tribal: one speculates how he would have presented the heroine, had he directed the film. As for Bimal Roy's Madhumati, she is something of a familiar archetype: an innocent who personifies nature itself, like Kalidasa's Shakuntala, like numerous other nymphs from Indian literature and cinema. This worn-out abstraction can become something startlingly immediate in Roy's hands. Throughout the film, one senses a search for the truth of Madhumati's elusive, protean nature, evoked most sublimely in the sequence where Anand follows her fugitive figure into the mist, drawn on by the music of her anklets. At this level, the film suggests that we are witnessing an eternal game of desire and yearning, stretching across centuries and lives. As always in Hindi cinema, it is the lyric writer who grasps its mystical essence: Main nadiya phir bhi main pyaasi / Bhed ye gehra, baat zara si. I am a river, yet I am thirsty / Simple words, but a deep mystery.

Rajesh Devraj

Precede

INDIAN NEWS REVIEW N° 172

(India/1952) D.: 9'. V. inglese

Il Cinema Ritrovato

Anni Cinquanta, l’età dell’oro. Classici Indiani da salvare

Anni Cinquanta, l’età dell’oro. Classici Indiani da salvare

Tariffe:

Aria condizionata

Info: 051224605