I TRE SPETTATORI CIECHI E L'ELEFANTE 1913

Sei ciechi vogliono capire, attraverso il tatto, che cos'è un elefante. A seconda della parte del corpo dell'animale che ciascuno di loro tocca, giungono a conclusioni totalmente diverse. L'elefante è come un serpente, dice il primo. No, dice il secondo, è come un ventaglio. Sciocchezze, dice il terzo, somiglia piuttosto a una colonna, o a un tronco... e così via. Noi spettatori abbiamo avuto reazioni simili davanti alla variegata produzione del 1913. A toccare in profondità l'animo del cinefilo è il capolavoro di un maestro (Peter von Bagh, Ingeborg Holm); il ricercatore e collezionista ci ha portato dal Giappone la rarità definitiva, il secondo film sopravvissuto di Stellan Rye, regista della cui produzione, fino a oggi, si conosceva solo Lo studente di Praga (Hiroshi Komatsu, Gendarm Möbius); e la curatrice del programma ancora oggi, dopo anni di lavoro e migliaia di film visti, chiede speranzosa a ogni singolo rullo che mette sulla moviola "Sorprendimi!": e la sua preghiera viene esaudita da film brevi e formidabili, spesso anonimi, spesso non-fiction (Mariann Lewinsky, Il mondo visibile e patafisico).

Six blind people want to find out, by touch, what an elephant looks like. They come to totally different conclusions, depending on which part of the body each of them has touched. The elephant is like a snake, says the first. No, says the second, it's like a fan. Nonsense, says the third, it's like a thick pillar or a tree-trunk... and so on. We viewers have similar reactions to the very diverse production of 1913. For the cinephile among us, the masterwork of an auteur of the film medium reached deep into his soul (Peter von Bagh, Ingeborg Holm), while our researcher and collector brought from Japan the ultimate rarity, the second surviving work of Stellan Rye, for until now the only film of his entire oeuvre known to exist was The Student from Prague (Hiroshi Kimatsu, Gendarm Möbius). The programme curator even now, after years on the job, viewing thousands of films, asks hopefully of every single reel she puts on the Steenbeck "Étonnez-moi!": and her plea is answered by wondrous short films, mostly anonymous, often non-fiction (Mariann Lewinsky, The Visible and the Pataphysical World).

Parte 1: Carte blanche a Peter von Bagh

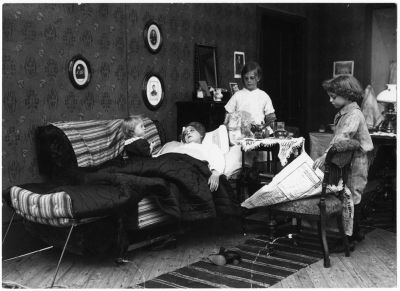

INGEBORG HOLM (Svezia/1913) R.: Victor Sjöström. D.: 73'

Accompagnamento al piano di Matti Bye

Sog.: dall'omonimo dramma di Nils Krok. Scen.: Nils Krok, Victor Sjöström. F.: Henrik Jaenzon. Int.: Hilda Borgström (Ingeborg Holm), Aron Lindgren (Sven Holm), Erik Lindholm (impiegato del negozio). Prod.: Svenska Biografteatern. 35mm. L.: 1326 m. D.: 73' a 16 f/s. Bn. Didascalie svedesi / Swedish intertitles

Da: Svenska Filminstitutet

Nel 1969, a partire da un negativo su nitrato, è stato tratto un interpositivo 35mm del film, che ha generato un duplicato negativo in formato academy nel 1973 . Successivamente un taglio di censura considerato perduto è stato ritrovato e inserito nel duplicato negativo, dal quale nel 1986 è stata ricavata la copia di questa proiezione . Le didascalie provengono da una serie completa conservata da Svenska Filminstitutet, e risalgono probabilmente a una data posteriore al 1913 / A 35mm full frame inter-positive was made from a nitrate negative source in 1969, from which a down-sized academy ratio duplicate negative was made in 1973. Sometime later, a previously lost censorship cut was discovered, and inserted into the duplicate negative, from which this viewing print was struck in 1986. The inter-titles in the film come from a complete set of title cards held in the non-film collections of the Svenska Filminstitutet, probably originating from a later date than 1913

Mi domando se ci sia nessun altro film del 1913 così duro, così definitivo nel suo enunciato sociale, o così moderno nel gesto quanto Ingeborg Holm. Il primo capolavoro di Sjöström è un film cristallizzato e nobile come Ladri di biciclette; è sapiente nella costruzione come un'opera di Mizoguchi, arrivando a mettere in scena una storia crudele quanto quella che ritroveremo in Vita di O-Haru, donna galante - una donna, emarginata dalla società (e a causa della società), viene violentemente separata dal proprio figlio biologico, e può vederlo solo a distanza. Anni dopo, il figlio ritorna dal mare. Porta con sé un ritratto della madre giovane, ma quella che ora incontra è una donna prematuramente invecchiata, rinchiusa in un ospedale psichiatrico... La follia, nel 1913, era già stata mostrata al cinema, ma solo per produrre impressioni forti, mai come la presentazione di un caso clinico. Ingeborg Holm si spinge ancora oltre: presenta a un tempo due for-me di malattia, il caso individuale di una donna sfortunata, punita per le sue modeste origini, e la malattia del corpo sociale. Lo straordinario registro narrativo e compositivo di Sjöström è già tutto qui: un duro e documentato quadro sociale si combina con la rappresentazione compiuta di una vita individuale, penetrando fin nel profondo d'una mente. Nessun altro, nella storia del cinema, era mai arrivato a tanto. Le sue strategie di messinscena padroneggiano l'intera gamma espressiva, dal naturalismo al linguaggio sperimentale, inclusa una sorprendente capacità di assorbire la lezione della miglior letteratura e del miglior teatro dell'epoca. Sjöström è tra i pochi giganti che hanno pienamente integrato il teatro nella propria concezione del cinema, pari in questo a Welles, a Bergman, a Visconti e ai pochissimi altri che hanno saputo usare la comprensione del teatro come fonte di un'espressione cinematografica doppiamente originale.

Peter von Bagh

I wonder if any film from 1913 is as tough, as total in its social commentary, or as modern in its gesture, as Ingeborg Holm. Sjöström's first masterpiece is as crystallized and noble as Bycicle Thief; it is as ingenious as anything from Mizoguchi, even creating a central situation every bit as hard as the toughest idea in The Life of O-Haru - a woman, separated violently from society (and by society) is taken away from her biological child, and can see him only from a distance. Years later the son returns from the sea. He has a picture of his mother as a young woman, but now he faces a prematurely old woman interned in a mental hospital... Insanity had been shown before in films, but only to shock, not as the presentation of a medical case. This vision indicates even more: two illnesses side by side, the individual case of an unhappy woman punished for her lowly social origins and the illness of the social body. Sjöström's exceptional range was there from the beginning: the combination of an actual (documented), tough social picture along with fully realized images of the individual, plunging into inner mental layers. No one else in film history had achieved this before him. His filmic strategies ranged the full scale, from naturalism to experimental, including an amazing capacity to absorb the lessons and achievements of the best literature and theater of the time. Sjöström belongs with the giants who fully integrated theater into their conception of filmmaking, equal to Welles, Bergman, Visconti and few others who could use their understanding of theater as a source of doubly original filmic expression.

Peter von Bagh

Parte 2: Carte blanche a Hiroshi Komatsu

GENDARM MÖBIUS (Germania/1913) R.: Stellan Rye. D.: 38'

Accompagnamento al piano di Donald Sosin

Sog.: dal romanzo di Victor Blüthgen. Scen.: Stellan Rye. Scgf.: Robert A . Dietrich. F.: Karl Hasselmann. Int.: Georg Molenar (gendarme Möbius), Lucie Höflich (Stina), Lothar Körner (Frans Lohmann), Victor Colani. Prod.: Deutsche Bioscop GmbH. 35mm. L.: 781 m. D.: 38' a 18 f/s. Bn. Didascalie inglesi / English intertitles

Da: National Film Center - The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (Komiya Collection)

Stellan Rye è oggi conosciuto solo come l'autore di Lo studente di Praga, ma realizzò molti film importanti nel periodo in cui fu primo regista della Künstler Filmserie alla Deutsche Bioscop, dal 1913 alla prima metà del 1914. Nato in Danimarca, autore di testi teatrali e sceneggiatore cinematografico a Copenhagen, a un certo punto fu coinvolto in uno scandalo e, dopo un periodo passato in prigione, lasciò la Danimarca e si stabilì a Berlino, dove cominciò una nuova vita come regista. Lavorò prima per la Eiko Film e poi per la Deutsche Bioscop, dove si dedicò esclusivamente alla Künstler Filmserie, serie pensata per i celebri attori della scena e collegata al movimento Autorenfilm. Rye morì in un ospedale da campo durante la Prima guerra mondiale: la sua carriera fu dunque assai breve ma prolifica - almeno quindici film in meno di due anni. La maggior parte apparteneva o si avvicinava al genere fantastico, come appunto Lo studente di Praga, e recava la forte impronta dello scrittore e sceneggiatore Hanns Heinz Evers. Gendarm Möbius è in questo senso un'eccezione, non v'è traccia qui di elementi fantastici. Tratto da un romanzo di Victor Blüthgen, il film narra la tragica storia del gendarme Möbius e della sua unica figlia Stina. La ragazza ha una relazione con un certo Lohmann, resta incinta, va in città per avere il bambino che però nasce morto, quindi decide di tornare a casa. Il film comincia da qui. Stina scopre che il suo amante si è nel frattempo fidanzato e il matrimonio è fissato per la sera seguente. Impazzita, appicca fuoco alla casa di Lohmann la notte delle nozze. Viene arrestata dal proprio padre, il gendarme Möbius: per salvare l'onore della famiglia, scelgono di morire insieme. Il film fu completato nel 1913, ma in Germania non venne distribuito fino al giugno 1914. Al contrario in Giappone, dove fu importato dalla Nierop Company, ebbe la sua première nel novembre del 1913, all'Odeon di Yokohama. Poiché la sua storia di onore e morte è molto giapponese, i giapponesi amarono Gendarm Möbius. Il critico Seji Ogava scrisse in "Kinema Record" (aprile 1914) che il percorso verso la morte dell'inflessibile e leale gendarme Möbius è realmente simile al Bushido giapponese.

Hiroshi Komatsu

Stellan Rye is only known as the director of The Student from Prague nowadays,but he worked for many important films as the chief film director of Künstler-Filmserie of Deutsche Bioscop from 1913 to the first half of 1914. Born in Denmark, he worked as a scriptwriter for theater and film in Copenhagen. After causing a scandal and the subsequent imprisonment, he fleed from Denmark and settled in Berlin. There he started his new life as a film director. He directed for Eiko Film first and then he moved to Deutsche Bioscop where he exclusively worked for the Künstler-Filmserie, film series for the renowned stage actors, which closely linked to so-called Autorenfilm movement. As he died at a field hospital during the WWI, his career as a film director was very short. However he was quite a prolific director. He made at least fifteen films in less than two years. Most of them belonged more or less to the fantastic film genre, just like The Student from Prague shows. The author and scriptwriter Hanns Heinz Ewers' taste was strongly impressed there. Gendarm Möbius was an exception. There is no fantastic elements here. Based on a Victor Blüthgen's novel, the story tells the tragedy of Gendarm Möbius and his only daughter Stina. Having an affair with Lohmann, Stina gets pregnant. She secretly goes to the city to have her baby. But it is born dead. She comes back home. [The film starts from here.] She finds that her lover Lohmann got engaged and the wedding will be celebrated the next evening. Getting mad, Stina sets fire to Lohmann's house in his wedding night. She is caught by her own father Gendarm Möbius: on account of the family honor, they choose their own death. The film was completed in 1913, but it was not released until June 1914 in Germany. In Japan, it was imported by Nierop Company and shown at Odeon Theater in Yokohama in November 1913. Because this story of honor is very much Japanese, Japanese audience liked it. The Japanese film critic Seiji Ogawa stated in "Kinema Record", April 1914, that the passage toward death of the extremely faithful and serious gendarm Möbius was really similar to Japanese Bushido's way.

Hiroshi Komatsu

Numero posti: 174

Aria Condizionata

Accesso e servizi per disabili

Il nostro cinema aderisce al circuito CinemAmico: è possibile utilizzare l’applicazione MovieReading® per i film di cui è prevista audiodescrizione e/o sottotitolazione sull'applicazione.

Tel. 051 2195311